Talk 4 | Religion for Atheists

When Jesus came into the world, it was a society complete with its gods and goddesses. Paganism was an entire way of life, where the deities of the ancient world and the practices of worship expressed visually what human life was about. With a loss of the Judeo‑Christian worldview we see in our western contemporary society today, we see that the rise in paganism is becoming deeply embedded. “The signs of this – the worship of Mammon (the god of money), Aphrodite (the goddess of erotic love), Mars (the god of violence) and many other deities – are engrained in the way we think, and in the assumptions, we make about how life works.” [1]

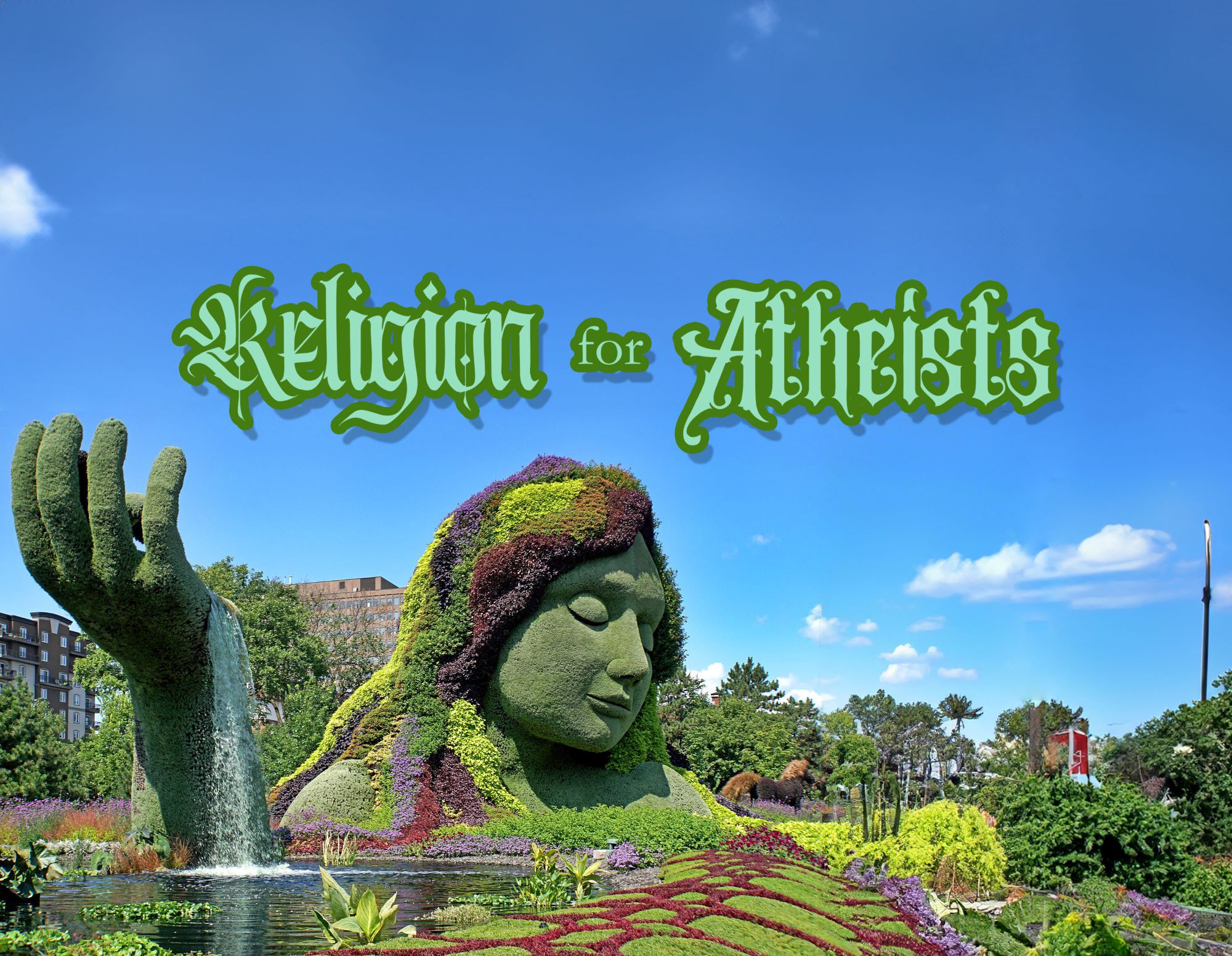

This is clearly seen in an increasingly accepted view of the environment. In pantheism, god is the universe (‘pan’ means ‘all’, ‘theism’ means ‘god’). The divine is an underlying spiritual unity and so the earth is an emanation of the divine. For many, the idea that our global ecosystem is to be treated as a single organism, has referred to it with the personal name “Gaia” (Greek for earth). In Greek Mythology, she is a personification of the earth – the ancestral matter – of all life, similar to the Roman Terra Mater (Mother Earth). Whatever is seen as divine becomes the lens through which we see reality. Mother Earth has become a goddess who is to be worshipped, because havoc is being reeked on the world because of the way humans have been treating her. The forces of nature and god are seen as synonymous.

According to this view, increasing spiritual oneness with nature will lead to a greater appreciation for all life. The syllabuses speak of students developing an eco‑identity, which refers to a portrait of oneself when relating to the non‑human natural environment. Two university professors, when looking at the direction of the curriculum in this area, made comments to the effect that the core premise of western culture is that humans are not the environment but are given dominion, and the failure to acknowledge the ecological in ourselves, has led to environmental crises. This is a rejection of the nature of humanity and their role in God’s world. This view of eco‑identity is the pathway to pantheism. “Both materialism and pantheism define ultimate reality in non‑personal terms.” [2] and reduce human personhood to no more value than plants and trees.

This worldview is idolatrous, as it substitutes the worship of the Creator because “They exchanged the truth of God for a lie and worshipped and served created things, rather than the Creator – who is forever praised. Amen.”(Romans 1: 25)

How, as Christian teachers, can we tell our story of the wonder of our Creator and the splendour and beauty of creation? How do we reaffirm the counter narrative, the Biblical view of the Creator, the creation and the place of humans as caretakers and cultivators of God’s world (Genesis 1: 28 – 30)? This is our eco-identity. The end purpose is that the earth shall be filled with the glory of the Lord.

The living God is the Creator of the world in all its beauty and design, but He is not part of creation. Earth was fine‑tuned to be the home for humanity, whom He created in His image. He then commanded Adam and Eve to serve as the stewards of His creation. The focus of the creation mandate is that human beings created in God’s image are called to develop society/culture/community that reflects the image of God. The task is civilisation and this is to be a picture of true human flourishing. In the Ancient world, human culture/settlement emerged in a particular place. For example, the people of Israel were to be a society/community who settled and lived according to God’s way in the land flowing with milk and honey (Deuteronomy 4: 1 – 8). This is different to the way our modern world sees creation. It is seen as nature which came into being through a random process of time and chance, seen predominantly as only the physical world and human life at a basic biological entity. Whereas the Bible sees all human society and culture as part of creation.

Underlying all human cultural activity is the nature of created reality “which both makes possible that activity and sets normative standards for it.” [3] As a community of neighbours, our redemptive task is to care for and cultivate culture in accord with the wisdom of the Creator. “We are called to participate in the ongoing creational work of God, to be God’s helper in executing to the end the blueprint for His masterpiece.” [4] Therefore, understanding sustainability is not a fear‑based societal script but a hope‑filled ethic.

The concept of sustainability is about how humans steward the environment with its patterns, processes and interdependencies, to build human settlement and culture that leads to human flourishing, as designed by God. The restoration and renewal of creation from evil is accomplished through His Gospel work. This transforming vision of life, God’s great re‑creation project, involves the task of cultivating culture and the earth. “We are meant to be the gardeners of God’s good world; we aren’t meant to leave it as we found it, but rather to discover its richness, unfold its goodness and add to its beauty. We are designed to be cultivators … in everything we do. Our achievements matter, because the culture we make lays down a track that someone else will run on.” [5]

When unfolding creation care and development that reflects the worship, wisdom and righteousness of God in a teaching program, it needs to:

- Search for truth about the physical environment as created by God to be the home for humanity.

- The impact, both positive and negative, that people can have on the environment; explore how human sin, greed and selfishness have caused havoc on the environment.

- Reject the notion that the earth, as a physical and biological reality, is more important than humanity. (Psalm 8:3-5)

- Explore what it means to care for and develop the creation, where humans and the physical environment can flourish. Guide students to evaluate their own values and actions and how they impact the creation.

- Explore the love of neighbour as it relates to human settlement and culture. For example, reducing the harmful effects of soil, water and air pollutants is love of neighbour for those who share our country and world.

- Conserving and enjoying the beauty of creation shows love for God. How can beauty be conserved when people build cities?

- Resist climate ideology alarmism that generates anxiety. Recognise that climate science is not equal to climate ideology. This false apocalyptic highlights all the terrible events such as droughts and floods whist ignoring the big picture. “The news headlines don’t tell us the facts that such climate related disasters have declined fifty-fold across the past century.”[6]

- Recognise that it is not the size of the human population that is the problem – it is the current rate of resource use and how they are distributed. To say that the world’s population should be reduced is to violate the creation mandate ‘to be fruitful and multiply’ (Genesis 1: 28), for sons and daughters are a heritage from the Lord, children a reward from Him. In the grand Biblical story, “generations are the pulse‑beats of humanity and every generation is close to God and responsible to God for its own times …” [7] Those who trust the God whose story is one of kept promises, have courage to bring new life into the world, no matter how dark the times.

- Guide students to evaluate their own values and actions and how they impact the creation.

- Explore issues of justice. For example, explore the dilemma which poor developing countries may face when exploitative companies destroy parts of their environment, which, in return, provides income and employment for their people.

Let us help our children and young people to act as culture‑makers who unfold the goodness and truth of our Creator and live according to the priorities of the Kingdom.

“For the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.” (Habakkuk 2: 14)

Grace and Peace,

The Excellence Centre Team

[1] Tom Wright, Spirituality and Religions – The Gospel in the Age of Paganism, (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2017), viii

[2] Nancy Pearcey, 129

[3] Albert M Wolters, Creation Regained -Biblical Basics for a Reformational Worldview, (Grand Rapids: Wm.B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005)

[4] Albert M Wolters, ibid, 37-38

[5] Dr Mark Stephens, Teaching for Humanity, (The Royale Ornsby Martin Lecture, 2016)

[6] Jordan Peterson & Bjorn Lomborg, The World is much better than it was, The Australian

[7] Os Guinness, Impossible People – Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization, (Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2016), 174